Tales of Saltykov Shchedrin list summary. Wise scribbler. General lack of school curriculum

The satirical tale "The Wise Minnow" ("The Wise Piskar") was written in 1882-1883. The work was included in the cycle "Tales for children of a fair age." In Saltykov-Shchedrin's fairy tale "The Wise Minnow", cowardly people who live in fear all their lives without doing anything useful are ridiculed.

main characters

wise scribbler- "enlightened, moderately liberal", lived for more than a hundred years in fear and loneliness.

Piskar's father and mother

“Once upon a time there was a scribbler. Both his father and mother were smart. Dying, the old scribbler taught his son to "look at both." The wise scribbler understood that dangers lay around him - a large fish could swallow it, cut the cancer with claws, torture the water flea. The scribbler was especially afraid of people - even his father once almost hit him in the ear.

Therefore, the scribbler carved a hole for himself, into which only he could fall. At night, when everyone was asleep, he went out for a walk, and during the day he “sat in a hole and trembled.” He was sleep deprived, malnourished, but avoided danger.

Somehow, the scribbler dreamed that he won two hundred thousand, but, waking up, found that half of his head had “poked out” of his hole. Almost every day, danger awaited him at the hole, and, having avoided another, he exclaimed with relief: “Thank you, Lord, he is alive!” ".

Fearing everything in the world, the piskar did not marry and had no children. He believed that earlier “and the pikes were kinder and the perches didn’t covet us, small fry,” so his father could still afford a family, and he “as if only to live on his own.”

The wise scribbler lived in this way for more than a hundred years. He had no friends or relatives. "He doesn't play cards, he doesn't drink wine, he doesn't smoke tobacco, he doesn't chase red girls." Already the pikes began to praise him, hoping that the squatter would listen to them and get out of the hole.

"How many years have passed after a hundred years - it is not known, only the wise scribbler began to die." Reflecting on his own life, the piskary realizes that he is “useless” and if everyone lived like this, then “the whole piskary family would have died out long ago”. He decided to get out of the hole and “swim like a gogol across the river”, but again he was frightened and trembled.

Fish swam past his hole, but no one was interested in how he lived to a hundred years. Yes, and no one called him wise - only "dumb", "fool and shame".

Piskar falls into oblivion, and then again he had a dream of old, how he won two hundred thousand, and even "grew by a whole polar inch and swallows the pike himself." In a dream, a piskar accidentally fell out of a hole and suddenly disappeared. Perhaps his pike swallowed it, but “most likely he died himself, because what sweetness is it for a pike to swallow an ailing, dying scribbler, and besides, a wise one?” .

Conclusion

In the fairy tale "The Wise Scribbler" Saltykov-Shchedrin reflected a contemporary social phenomenon common to him among the intelligentsia, which was concerned only with its own survival. Despite the fact that the work was written more than a hundred years ago, it does not lose its relevance today.

Fairy tale test

Test your knowledge of the summary with the test:

Retelling rating

Average rating: four . Total ratings received: 2017.

Mikhail Evgrafovich Saltykov-Shchedrin wrote: “... Literature, for example, can be called Russian salt: what will happen if salt ceases to be salty, if it adds voluntary self-restraint to restrictions that do not depend on literature ...”

This article is about the fairy tale by Saltykov-Shchedrin "Konyaga". In a brief summary, we will try to understand what the author wanted to say.

about the author

Saltykov-Shchedrin M. E. (1826-1889) - an outstanding Russian writer. Born and spent his childhood in a noble estate with many serfs. His father (Evgraf Vasilyevich Saltykov, 1776-1851) was a hereditary nobleman. Mom (Zabelina Olga Mikhailovna, 1801-1874) was also from a noble family. After receiving his primary education, Saltykov-Shchedrin entered the Tsarskoye Selo Lyceum. After graduation, he began his career as a secretary in the military office.

In life, moving up in the service, he traveled a lot through the provinces and observed the desperately plight of the peasantry. Having a pen as a weapon, the author shares what he has seen with his reader, denouncing lawlessness, tyranny, cruelty, lies, immorality. Revealing the truth, he wanted the reader to be able to consider a simple truth behind a huge shaft of lies and myths. The writer hoped that the time would come when these phenomena would decrease and disappear, since he believed that the fate of the country was in the hands of the common people.

The author is outraged by the injustice happening in the world, the powerless, humiliated existence of serfs. In his works, he sometimes allegorically, sometimes directly denounces cynicism and callousness, stupidity and megalomania, greed and cruelty of those in power and authority at that time, the plight and hopeless situation of the peasantry. Then there was strict censorship, so the writer could not openly criticize the established state of affairs. But he could not endure in silence, like a "wise gudgeon", so he clothed his thoughts in a fairy tale.

Tale of Saltykov-Shchedrin "Konyaga": a summary

The author writes not about a slender horse, not about a submissive horse, not about a fine mare, and not even about a hard worker horse. And about the goner-horse, poor fellow, hopeless, meek slave.

How does he live, Saltykov-Shchedrin wonders in Konyaga, without hope, without joy, without the meaning of life? Where does he get strength for the daily hard labor of endless labor? They feed him and let him rest only so that he does not die and can still work. Even from the brief content of the fairy tale "Konyaga" it is clear that the serf is not a person at all, but a labor unit. “... It is not his well-being that is needed, but a life capable of enduring the yoke of work ...” And if you do not plow, who needs you, only damage to the economy.

Weekdays

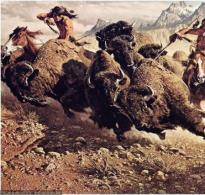

In a brief summary of the “Konyaga”, first of all, it is necessary to tell how the stallion does his job monotonously all year round. From day to day the same thing, furrow after furrow, with the last of his strength. The field does not end, do not plow plow. For someone field-space, for the horse - bondage. Like a "cephalopod", it sucked and pressed, taking away strength. Hard bread. But he doesn't exist either. Like water in dry sand: it was and is not.

And probably there was a time when a horse frolic like a foal on the grass, played with the breeze and thought how beautiful, interesting, deep life is, how it sparkles with different colors. And now he lies thin in the sun, with protruding ribs, with shabby hair and bleeding wounds. Mucus flows from the eyes and nose. Before the eyes of darkness and lights. And around the flies, gadflies, stuck around, drinking blood, climb into the ears, eyes. And you have to get up, the field is not plowed up, and there is no way to get up. Eat, they tell him, you won't be able to work. And there’s no strength to reach out to food, he won’t even move his ear.

Field

Wide expanses, covered with greenery and ripe wheat, are fraught with a huge magical power of life. She is chained in the ground. Freed, she would have healed the horse's wounds, removed the burden of worries from the peasant's shoulders.

In a brief summary of the "Konyaga" one cannot fail to tell how a horse and a peasant work on it day after day, like bees, giving their sweat, their strength, time, blood and life. For what? Wouldn't even a small fraction of the great power be enough for them?

Waste dances

In the summary of Saltykov-Shchedrin's "Konyaga" one cannot help but show horses-dancing. They consider themselves the chosen ones. Molded straw is for horses, and for them only oats. And they will be able to substantiate this competently, and convince that this is the norm. And their horseshoes are probably gilded and their manes are silky. They frolic in the expanse, creating for everyone the myth that the father-horse planned it that way: for one everything, for the other only a minimum, so that labor units do not die. And suddenly it is revealed to them that they are alluvial foam, and the peasant with the horse, who feed the whole world, are immortal. "How so?" - empty dancers will cackle, they will be surprised. How can a horse with a peasant be eternal? Where does their virtue come from? Each empty dance inserts its own. How can such an incident be justified for the world?

“Yes, he’s stupid, this man, he plows in the field all his life, where does the mind come from?” - something like this says one. In modern terms: "If so smart, why no money?" And what about the mind? The strength of the spirit is enormous in this frail body. “Labor gives him happiness and peace,” the other reassures himself. “Yes, he won’t be able to live in any other way, he’s used to the whip, take it away and he’ll disappear,” develops the third. And having calmed down, they joyfully wish, as if for the good of the disease: “... That's who you need to learn from! Here's who to imitate! N-but, hard labor, n-but!

Conclusion

The perception of the fairy tale "Konyaga" by Saltykov-Shchedrin is different for each reader. But in all his works, the author pities the common man or denounces the shortcomings of the ruling class. In the image of Konyaga and Peasant, the author has resigned, oppressed serfs, a huge number of working people who earn their little penny. “... How many centuries he bears this yoke - he does not know. How many centuries it is necessary to carry it ahead - does not count ... ”The content of the fairy tale“ Konyaga ”is like a brief digression into the history of the people.

In this work, which the tongue does not dare to call a fairy tale, the story turned out to be too sad, Saltykov-Shchedrin describes the life of a peasant horse, Konyaga. Symbolically, the image of Konyaga refers to the peasants, whose work is just as exhausting and hopeless. The text can be used for a reader's diary, shorten it a little more if necessary.

The tale begins with the fact that Konyaga lies by the road after the arable land of a difficult rocky strip and dozes. His owner gave him a break so that the animal could eat, but Konyaga no longer had the strength to eat.

The following is a description of Konyaga: an ordinary workhorse, tortured, with a fallen mane, sore eyes, broken legs and burned shoulders, very thin - the ribs stick out. The horse works from morning to evening - it plows in the summer, and in the winter they deliver goods for sale on it - “carries works”.

They feed and care for him poorly, so he has nowhere to gain strength. If in the summer it is still possible to pinch the grass, then in the winter the Konyaga eats only rotten straw. Therefore, by the spring he is completely exhausted, for work in the field he has to be raised with the help of poles.

But still, Konyaga was lucky with the owner - he is a kind man and in vain "he does not cripple him." They both work to the point of exhaustion: "they will go through the furrow from end to end - and both tremble: here it is, death, has come!"

Further, Saltykov-Shchedrin describes a peasant settlement - in the center there is a narrow road (country road) that connects the villages, and along the edges there are endless fields. The author compares the fields with an immovable mass, inside which there should be a fabulous power, as if imprisoned in captivity. And no one can release this power, because after all, this is not a fairy-tale work, but real life. Although the peasant and Konyaga have been fighting over this task all their lives, the strength is not released, and the bonds of the peasant do not fall off, and the shoulders of the Konyaga are not healed.

Now Konyaga lies in the sun and suffers from the heat. Flies and gadflies bite him, everything hurts inside, but he cannot complain. "And in this joy, God denied the dumb animal." And rest for him is not rest at all, but agony; and a dream is not a dream, but an incoherent “gloom” (this word symbolically means oblivion, but in fact in Old Russian it meant a cloud, cloud, fog).

Konyaga has no choice, the field in which he works is endless, although he proceeded from it in all directions. For people, the field is space and "poetry", and for our heroes it is bondage. Yes, and nature for Konyaga is not a mother, but a tormentor - the hot rays of the sun burn mercilessly, frost, wind and other manifestations of the natural elements also torment him. All he can feel is pain and fatigue.

It was created for hard work, this is the meaning of its existence. There is no end to his work, therefore both food and rest are given to him exactly at the level so that he still continues to somehow live and can physically work.

Past him, lying and exhausted, empty dances pass - this is how the author calls the horses, which have a different fate. Although they are brothers, Konyaga was born rude and insensitive, and Pustoplyas, on the contrary, sensitive and courteous. And so the old horse, their father, ordered Konyaga to work, eat only rotten straw and drink from a dirty puddle, while the other son was always in a warm stall, on soft straw and ate oats. As you might guess, in the image of idle dances, Saltykov-Shchedrin depicts other sections of society - nobles and landowners who do not need to work so hard.

Further in the fairy tale, idle dancers discuss Konyaga, talk about the reasons for his immortality - although they beat him mercilessly, and he works without rest, but for some reason he still lives. The first empty dance believes that Konyaga developed common sense from work, from which he simply resigned himself. The second considers Konyaga the bearer of the life of the spirit and the spirit of life. These two spiritual treasures allegedly make the horse invulnerable. The third says that Konyaga found meaning in his work, but idle dances have long lost such meaning. The fourth believes that the horse has long been accustomed to pulling his strap, although life is barely glimmering in him, but you can always cheer him up with a whip. And there are many horses like that, they are all the same, use their work as much as you like, they will not go anywhere.

But their argument is interrupted at the most interesting place - a man wakes up, and his cry wakes up Konyaga. And here the idle dancers are delighted, admire how the animal is trying to rise, and even advise learning from it. “B-but, convict, n-but!” With these words the story ends.

Other retellings of Saltykov-Shchedrin's fairy tales:

Sheep-not remembering

The forgetful ram is the hero of a fairy tale. He began to see vague dreams that disturbed him, forcing him to suspect that "the world does not end with the walls of a barn." The sheep began mockingly calling him "wise man" and "philosopher" and shunned him. The ram withered and died. Explaining what had happened, the shepherd Nikita suggested that the deceased "saw a free-ram in a dream."

Bogatyr

The hero is the hero of a fairy tale, the son of Baba Yaga. Sent by her to exploits, he uprooted one oak tree, crushed another with his fist, and when he saw the third, with a hollow, he climbed in there and fell asleep, frightening the neighborhood with snoring. His fame was great. The hero was both afraid and hoped that he would gain strength in a dream. But centuries passed, and he was still sleeping, not coming to the aid of his country, no matter what happened to it. When, during an enemy invasion, they approached him to help him out, it turned out that the Bogatyr had long been dead and rotted. His image was so clearly aimed against the autocracy that the tale remained unpublished until 1917.

wild landlord

The wild landowner is the hero of the fairy tale of the same name. Having read the retrograde newspaper Vest, he foolishly complained that "there are too many divorced ... peasants," and tried in every possible way to oppress them. God heard the tearful peasant prayers, and "there was no peasant in the entire space of the possessions of the stupid landowner." He was delighted (the “clean” air became), but it turned out that now he could neither receive guests, nor eat himself, nor even wipe the dust from the mirror, and there was no one to pay taxes to the treasury. However, he did not deviate from his "principles" and as a result, he became wild, began to move on all fours, lost human speech and became like a predatory beast (once he did not bully the police officer himself). Worried about the lack of taxes and the impoverishment of the treasury, the authorities ordered "to catch the peasant and put him back." With great difficulty they also caught the landowner and brought him to a more or less decent appearance.

Karas-idealist

Karas-idealist - the hero of the fairy tale of the same name. Living in a quiet backwater, he is sympathetic and cherishes dreams of the triumph of good over evil, and even of the opportunity to reason with Pike (whom he has never seen) that she has no right to eat others. He eats shells, justifying himself by the fact that "they climb into their mouths" and they have "not a soul, but steam." Having appeared before Pike with his speeches, for the first time he was released with the advice: "Go to sleep!" In the second, he was suspected of "sicilism" and pretty much bitten during interrogation by Okun, and the third time, Pike was so surprised at his exclamation: "Do you know what virtue is?" - that she opened her mouth and almost involuntarily swallowed her interlocutor. "In the image of Karas, the features of modern liberalism are grotesquely captured by the writer. Ruff is also a character in this fairy tale. He looks at the world with bitter sobriety, seeing strife and savagery everywhere. Karas ironically over the reasoning, convicting him of perfect ignorance of life and inconsistency (Karas is indignant at Pike, but eats shells himself. However, he admits that "after all, you can talk with him alone," and at times even slightly hesitates in his skepticism, until the tragic outcome of the "dispute" Carp with Pike does not confirm his innocence.

sane hare

The sensible hare - the hero of the fairy tale of the same name, "reasoned so sensibly that it fit the donkey." He believed that "every animal has its own life" and that, although "everyone eats" hares, he is "not picky" and "agrees to live in every possible way." In the heat of this philosophizing, he was caught by the Fox, who, bored with his speeches, ate him.

Kissel

Kissel, the hero of the fairy tale of the same name, "was so flamboyant and soft that he did not feel any inconvenience from what he ate. The gentlemen were so fed up with them that they provided pigs with food, so, in the end, "only jelly was left dried scrapes", In a grotesque form, both peasant humility and the post-reform impoverishment of the village, robbed not only by the "master" landowners, but also by new bourgeois predators, who, according to the satirist, like pigs, "satiety ... do not know ".

BARAN-NEPOMNYASHCHY

The forgetful ram is the hero of a fairy tale. He began to see vague dreams that disturbed him, forcing him to suspect that "the world does not end with the walls of a barn." The sheep began mockingly calling him "wise man" and "philosopher" and shunned him. The ram withered and died. Explaining what had happened, the shepherd Nikita suggested that the deceased "saw a free ram in a dream."

BOGATYR

The hero is the hero of a fairy tale, the son of Baba Yaga. Sent by her to exploits, he uprooted one oak tree, crushed another with his fist, and when he saw the third, with a hollow, he climbed in there and fell asleep, frightening the neighborhood with snoring. His fame was great. The hero was both afraid and hoped that he would gain strength in a dream. But centuries passed, and he was still sleeping, not coming to the aid of his country, no matter what happened to it. When, during an enemy invasion, they approached him to help him out, it turned out that the Bogatyr had long been dead and rotted. His image was so clearly aimed against the autocracy that the tale remained unpublished until 1917.

WILD LANDMAN

The wild landowner is the hero of the fairy tale of the same name. Having read the retrograde newspaper Vest, he foolishly complained that "there are too many divorced ... peasants," and tried in every possible way to oppress them. God heard the tearful peasant prayers, and "there was no peasant in the entire space of the possessions of the stupid landowner." He was delighted (the “clean” air became), but it turned out that now he could neither receive guests, nor eat himself, nor even wipe the dust from the mirror, and there was no one to pay taxes to the treasury. However, he did not deviate from his "principles" and as a result, he became wild, began to move on all fours, lost human speech and became like a predatory beast (once he did not bully the police officer himself). Worried about the lack of taxes and the impoverishment of the treasury, the authorities ordered "to catch the peasant and put him back." With great difficulty they also caught the landowner and brought him to a more or less decent appearance.

KARAS-IDEALIST

Karas-idealist - the hero of the fairy tale of the same name. Living in a quiet backwater, he is sympathetic and cherishes dreams of the triumph of good over evil, and even of the opportunity to reason with Pike (whom he has never seen) that she has no right to eat others. He eats shells, justifying himself by the fact that "they climb into their mouths" and they have "not a soul, but steam." Having appeared before Pike with his speeches, for the first time he was released with the advice: "Go to sleep!" In the second, he was suspected of "sicilism" and pretty much bitten during interrogation by Okun, and the third time, Pike was so surprised at his exclamation: "Do you know what virtue is?" - that she opened her mouth and almost involuntarily swallowed her interlocutor. "The features of contemporary liberalism are grotesquely captured in the image of Karas.

SANITARY HARE

The sensible hare - the hero of the fairy tale of the same name, "reasoned so sensibly that it fit the donkey." He believed that "every animal has its own life" and that, although "everyone eats" hares, he is "not picky" and "agrees to live in every possible way." In the heat of this philosophizing, he was caught by the Fox, who, bored with his speeches, ate him.

KISSEL

Kissel, the hero of the fairy tale of the same name, "was so flamboyant and soft that he did not feel any inconvenience from what he ate. The gentlemen were so fed up with them that they provided pigs with food, so, in the end, "only jelly was left dried scrapes". In a grotesque form, both peasant humility and the post-reform impoverishment of the village, robbed not only by the "masters" - landlords, but also by new bourgeois predators, who, according to the satirist, like pigs, "satiety ... do not know ".

The generals are characters in "The Tale of How One Man Feeded Two Generals." Miraculously, they found themselves on a desert island in the same nightgowns and with orders around their necks. They couldn’t do anything and, starving, they almost ate each other. Having changed their minds, they decided to look for a peasant and, having found it, demanded that he feed them. In the future, they lived by his labors, and when they got bored, he built "such a vessel so that you could swim across the ocean-sea." Upon returning to St. Petersburg, G. received a pension accumulated over the past years, and a glass of vodka and a nickel of silver were granted to their breadwinner.

Ruff is a character in the fairy tale "Karas-Idealist". He looks at the world with bitter sobriety, seeing strife and savagery everywhere. Karas ironically over the reasoning, convicting him of complete ignorance of life and inconsistency (Karas is indignant at Pike, but eats shells himself). However, he admits that “after all, you can talk with him alone to your liking,” and at times even slightly hesitates in his skepticism, until the tragic outcome of the “dispute” between Karas and Pike confirms his innocence.

Liberal is the hero of the fairy tale of the same name. “He was eager to do a good deed,” but out of apprehension he moderated his ideals and aspirations more and more. At first, he acted only “if possible”, then agreeing to receive “at least something” and, finally, acting “in relation to meanness”, consoling himself with the thought: “Today I’m wallowing in the mud, and tomorrow the sun will come out, dry the dirt - I’m done again -Well done!" The eagle-philanthropist is the hero of the fairy tale of the same name. He surrounded himself with a whole court staff and even agreed to start sciences and arts. However, he soon got tired of this (however, the Nightingale was driven out immediately), and he brutally cracked down on the Owl and the Falcon, who tried to teach him to read and write and arithmetic, imprisoned the historian Woodpecker in a hollow, etc. The wise scribbler is the hero of the fairy tale of the same name, “enlightened, moderately -liberal". From childhood, he was frightened by his father's warnings about the danger of getting into the ear and concluded that "you need to live in such a way that no one notices." He dug a hole in order to fit himself, did not make any friends or family, lived and trembled, having received in the end even pike praises: “Now, if everyone lived like that, it would be quiet in the river!” It was only before his death that the “wise man” realized that in such a case “perhaps the entire screech family would have died out long ago.” The story of the wise scribbler in exaggerated form expresses the meaning, or rather the entire nonsense, of the cowardly attempts to "dedicate oneself to the cult of self-preservation," as the book Abroad says. The features of this character are clearly visible, for example, in the heroes of Modern Idyll, in Polozhilov and other Shchedrin heroes. The remark made by the then critic in the Russkiye Vedomosti newspaper is also characteristic: “We are all more or less scribblers ...”

WISE PISKAR

The wise scribbler is the "enlightened, moderately liberal" hero of the tale. From childhood, he was frightened by his father's warnings about the danger of getting into the ear and concluded that "you need to live in such a way that no one notices." He dug a hole, just to fit himself, did not make any friends or family, lived and trembled, Having received even pike praise in the end: "Now, if everyone lived like that, it would be quiet in the river!" It was only before his death that the “wise man” realized that in this case, “perhaps the entire piss-kary family would have died out long ago.” The story of the wise scribbler in exaggerated form expresses the meaning, or rather the entire nonsense, of the cowardly attempts to "devote oneself to the cult of self-preservation," as it is said in the book Abroad. The features of this character are clearly visible, for example, in the heroes of "Modern Idyll", in Polozhilov and other Shchedrin heroes. Characteristic is the remark made by the then critic in the Russkiye Vedomosti newspaper: "We are all more or less scribblers..."

Pustoplyas is a character in the fairy tale "Konyaga", the "brother" of the hero, unlike him, leading an idle life. The personification of the local nobility. The arguments of idle dancers about Konyaga as the embodiment of common sense, humility, “life of the spirit and spirit of life”, etc., are, as a contemporary critic wrote to the writer, “an insulting parody” of the then theories that sought to justify and even glorify “hard labor” peasants, their downtroddenness, darkness and passivity.

Ruslantsev Seryozha - the hero of the "Christmas Tale", a ten-year-old boy. After preaching about the need to live according to the truth, said, as the author seems to remark in passing, “for the holiday,” S. decided to do so. But both the mother, the priest himself, and the servants warn him that "one must live with the truth looking back." Shocked by the discrepancy between high words (indeed - a Christmas tale!) and real life, stories about the sad fate of those who tried to live by the truth, the hero fell ill and died. The selfless hare is the hero of the fairy tale of the same name. Caught by the Wolf and meekly sitting in anticipation of his fate, not daring to run even when the brother of his bride comes for him and says that she is dying of grief. Released to see her, he returns, as he promised, receiving condescending wolf praise.

Toptygin 1st - one of the heroes of the fairy tale "The Bear in the Voivodeship". He dreamed of capturing himself in history with a brilliant atrocity, but with a hangover he mistook a harmless siskin for an “internal adversary” and ate it. He became a universal laughingstock and was no longer able to improve his reputation even with his superiors, no matter how hard he tried - “he climbed into the printing house at night, smashed the machines, mixed the type, and dumped the works of the human mind into the waste pit.” "And if he started right from the printing houses, he would be ... a general."

Toptygin 2nd - a character in the fairy tale "The Bear in the Voivodeship". Arriving at the voivodeship in the hope of destroying the printing house or burning down the university, he found that all this had already been done. I decided that it was no longer necessary to eradicate the "spirit", but "to be taken straight for the skin." Having climbed up to a neighboring peasant, he pulled up all the cattle and wanted to destroy the yard, but he was caught and planted in disgrace on a horn.

Toptygin the 3rd is a character in the fairy tale "The Bear in the Voivodeship". I faced a painful dilemma: “If you mess up a little, they will ridicule you; if you mess up a lot, they’ll raise it on a horn ... ”Arriving at the voivodeship, he hid in a den, without taking control, and found that even without his intervention everything in the forest was going on as usual. He began to leave the lair only “to receive the appropriated maintenance” (although in the depths of his soul he wondered “why the governor was sent”). Later he was killed by hunters, like "all fur-bearing animals", also in a routine manner.