Alaska Natives. Russian-Indian wars Novoarkhangelsk - the capital of Russian America

The development of the lands of Alaska by Russian colonists began at the end of the 18th century. Moving south along the mainland coast of Alaska in search of richer fishing grounds, Russian parties of hunters for sea animals gradually approached the territory inhabited by the Tlingit, one of the most powerful and formidable tribes of the Northwest coast. The Russians called them Koloshi (Kolyuzhs). This name comes from the custom of Tlingit women to insert a wooden plank - kaluga - into the cut on the lower lip, which made the lip stretch and sag. “More evil than the most predatory animals”, “a murderous and evil people”, “bloodthirsty barbarians” - in such expressions the Russian pioneers spoke about the Tlingits.

And they had their reasons for that.

By the end of the XVIII century. The Tlingit occupied the coast of southeastern Alaska from the Portland Canal in the south to Yakutat Bay in the north, as well as the adjacent islands of the Alexander Archipelago.

The Tlingit country was divided into territorial divisions - kuans (Sitka, Yakutat, Huna, Khutsnuvu, Akoy, Stikine, Chilkat, etc.). Each of them could have several large winter villages, where representatives of various clans (clans, sibs) lived, belonging to two large phratries of the tribe - the Wolf / Eagle and the Raven. These clans - Kiksadi, Kagwantan, Deshitan, Tluknahadi, Tekuedi, Nanyaayi, etc. - were often at enmity with each other. It was tribal, clan ties that were the most significant and strong in Tlingit society.

The first clashes between the Russians and the Tlingit date back to 1741, later there were also small skirmishes with the use of weapons.

In 1792, an armed conflict took place on Hinchinbrook Island with an uncertain result: the head of the party of industrialists and the future ruler of Alaska, Alexander Baranov, almost died, the Indians retreated, but the Russians did not dare to gain a foothold on the island and also sailed to Kodiak Island. Tlingit warriors were dressed in wicker wooden kuyaks, elk cloaks and animal-like helmets (apparently made from animal skulls). The Indians were armed mainly with cold and throwing weapons.

If during the attack on the party of A. A. Baranov in 1792 the Tlingits had not yet used firearms, then already in 1794 they had a lot of guns, as well as decent stocks of ammunition and gunpowder.

Treaty of Peace with the Indians of Sitka

Russians in 1795 appear on the island of Sitka, which was owned by the Kiksadi Tlingit clan. Closer contacts began in 1798.

After several minor clashes with small detachments of kiksadi, led by the young military leader Katlean, Alexander Andreevich Baranov concludes an agreement with the leader of the kiksadi tribe, Scoutlelt, to acquire land for the construction of a trading post.

Scoutlelt was baptized and his name became Michael. Baranov was his godfather. Scoutlelt and Baranov agreed to cede part of the land on the coast to the Russians and build a small trading post at the mouth of the Starrigavan River.

The alliance between the Russians and the Kiksadi was beneficial to both sides. The Russians patronized the Indians and helped them protect themselves from other warring tribes.

On July 15, 1799, the Russians began building the fort "St. Michael the Archangel", now this place is called Staraya Sitka.

Meanwhile, the Kiksadi and Deshitan tribes concluded a truce - the hostility between the Indian clans ceased.

The danger to the Kixadi was gone. Too close contact with the Russians is now becoming too burdensome. Both the Kiksadi and the Russians felt this very soon.

Tlingit from other clans who visited Sitka after the cessation of hostilities there, mocked its inhabitants and "boasted of their freedom." The biggest quarrel occurred on Easter, however, thanks to the decisive actions of A.A. Baranov, bloodshed was avoided. However, on April 22, 1800, A.A. Baranov departed for Kodiak, leaving V.G. Medvednikov.

Despite the fact that the Tlingit had rich experience of communicating with Europeans, relations between the Russian settlers and the natives became more and more aggravated, which ultimately led to a protracted bloody war. However, such a result was by no means just an absurd accident or a consequence of the intrigues of insidious foreigners, just as these events were not generated by the only natural bloodthirstiness of the “fierce ears”. The Tlingit Kuans brought other, deeper causes onto the warpath.

Background of the war

Russian and Anglo-American merchants had one goal in the local waters, one main source of profit - furs, sea otters. But the means to achieve this goal were different. The Russians themselves mined precious furs, sending parties of Aleuts after them and founding permanent fortified settlements in the fishing areas. Buying skins from the Indians played a secondary role.

Due to the specifics of their position, British and American (Boston) merchants acted in exactly the opposite way. They periodically came on their ships to the shores of the Tlingit country, conducted active trade, bought furs and left, leaving fabrics, weapons, ammunition, and alcohol to the Indians in return. The ban on the sale of firearms among the Russians pushed the Tlingit to even closer ties with the Bostonians. For this trade, the volume of which was constantly growing, the Indians needed more and more furs. However, the Russians with their activities prevented the Tlingit from trading with the Anglo-Saxons.

The active fishing of the sea otter, which was carried out by Russian parties, was the reason for the impoverishment of the natural resources of the region, depriving the Indians of their main commodity in relations with the Anglo-Americans. All this could not but affect the attitude of the Indians towards the Russian colonists. The Anglo-Saxons actively fueled their hostility.

Every year, about fifteen foreign ships took out 10-15 thousand sea otters from the possessions of the RAC, which was equal to four years of Russian fishing. The strengthening of the Russian presence threatened them with deprivation of profits.

Thus, the predatory fishing of the sea animal, which was launched by the Russian-American Company, undermined the basis of the economic well-being of the Tlingit, depriving them of their main commodity in profitable trade with the Anglo-American sea traders, whose inflammatory actions served as a kind of catalyst that hastened the unleashing of the imminent military conflict. The rash and rude actions of Russian industrialists served as an impetus for the unification of the Tlingits in the struggle to expel the RAC from their territories.

In the winter of 1802, a great council of leaders took place in Hutsnuwu-kuan (Father Admiralty), at which a decision was made to start a war against the Russians. The council developed a plan of military action. It was planned with the onset of spring to gather soldiers in Khutsnuva and, after waiting for the fishing party to leave Sitka, attack the fort. The party was to lie in wait in the Dead Strait.

Hostilities began in May 1802 with an attack at the mouth of the Alsek River on the Yakutat fishing party of I.A. Kuskov. The party consisted of 900 native hunters and more than a dozen Russian industrial hunters. The attack of the Indians, after several days of skirmishing, was successfully repulsed. The Tlingit, seeing the complete failure of their warlike plans, went to negotiations and concluded a truce. The uprising of the Tlingit - the destruction of the Mikhailovsky Fort and Russian fishing parties

After the fishing party of Ivan Urbanov (about 190 Aleuts) left the Mikhailovsky Fort, 26 Russians, six "Englishmen" (American sailors in the service of the Russians), 20-30 Kodiaks and about 50 women and children remained on Sitka. On June 10, a small artel under the command of Alexei Evglevsky and Alexei Baturin went hunting to the “distant Siuchy stone”. Other inhabitants of the settlement continued to carelessly go about their daily business.

The Indians attacked simultaneously from two sides - from the forest and from the side of the bay, sailing on war canoes. This campaign was led by the military leader of the Kiksadi, the nephew of Scoutlelt, the young leader - Katlian. An armed mob of Tlingit, numbering about 600 people, under the command of the leader of the Sitka Scoutlelt, surrounded the barracks and opened heavy rifle fire at the windows. At the call of Scoutlelt, a huge flotilla of war canoes came out from behind the cape of the bay, on which there were at least 1000 Indian warriors, who immediately joined the Sitkins. Soon the roof of the barracks caught fire. The Russians tried to shoot back, but could not resist the overwhelming superiority of the attackers: the doors of the barracks were knocked out and, despite the direct fire of the cannon that was inside, the Tlingits managed to get inside, kill all the defenders and plunder the furs stored in the barracks

There are various versions of the participation of the Anglo-Saxons in unleashing the war.

In 1802, the East Indian captain Barber landed six sailors on the island of Sitka, allegedly for a mutiny on the ship. They were taken to work in a Russian city.

Having bribed the Indian chiefs with weapons, rum, and knick-knacks during their long winter stay in the Tlingit villages, promising them gifts if they drove the Russians from their island, and threatening not to sell guns and whiskey, Barber played on the ambitions of the young military leader Catlean. The gates of the fort were opened from the inside by American sailors. So, naturally, without warning or explanation, the Indians attacked the fortress. All defenders, including women and children, were killed.

According to another version, the real instigator of the Indians should be considered not the Englishman Barber, but the American Cunningham. He, unlike Barber and the sailors, ended up on Sitka clearly not by chance. There is a version that he was initiated into the plans of the Tlingit, or even participated directly in their development.

The fact that foreigners will be declared responsible for the Sitka disaster was predetermined from the very beginning. But the reasons for the fact that the Englishman Barber was then recognized as the main culprit lie probably in the uncertainty in which Russian foreign policy was in those years.

The fortress was completely destroyed, and the entire population was exterminated. Nothing is being built there yet. The losses for Russian America were significant, for two years Baranov was gathering strength in order to return to Sitka.

The news of the destruction of the fortress was brought to Baranov by the English captain Barber. Off Kodiak Island, he deployed 20 guns from the side of his ship, the Unicorn. But, afraid to get involved with Baranov, he went to the Sandwich Islands - to trade with the Hawaiians the good looted in Sitka.

A day later, the Indians almost completely destroyed the small party of Vasily Kochesov, who was returning to the fortress from the sea lions.

The Tlingit had a special hatred for Vasily Kochesov, the famous hunter, known among the Indians and Russians as an unsurpassed marksman. The Tlingit called him Gidak, which probably comes from the Tlingit name of the Aleuts, whose blood flowed in Kochesov's veins - giyak-kwaan (the hunter's mother was from the Fox Range Islands). Having finally got the hated archer into their hands, the Indians tried to make his death, like the death of his comrade, as painful as possible. According to K.T. Khlebnikov, “the barbarians, not suddenly, but temporarily, cut off their nose, ears and other members of their body, stuffed their mouths with them, and viciously mocked the torment of the sufferers. Kochesov ... could not endure pain for a long time and was happy at the end of his life, but the unfortunate Eglevsky languished in terrible torment for more than a day.

In the same year, 1802: Ivan Urbanov's Fishing Sitka party (90 kayaks) was tracked down by the Indians in the Frederick Strait and attacked on the night of June 19-20. Lurking in ambushes, the warriors of Kuan Keik-Kuyu did not betray their presence in any way and, as K.T. Khlebnikov wrote, “the leaders of the party did not notice any troubles or reasons for displeasure ... But this silence and silence were the harbingers of a cruel thunderstorm.” The Indians attacked the party members at the lodging for the night and "almost killed them with bullets and daggers." 165 Kodiaks were killed in the massacre, and this was no less a heavy blow to the Russian colonization than the destruction of the Mikhailovskaya fortress.

Russian return to Sitka

Then came 1804, the year the Russians returned to Sitka. Baranov learned that the first Russian round-the-world expedition had set out to sea from Kronstadt, and he was looking forward to the arrival of the Neva in Russian America, while at the same time building a whole fleet of ships.

In the summer of 1804, the ruler of the Russian possessions in America, A.A. Baranov went to the island with 150 industrialists and 500 Aleuts in his kayaks and with the ships Ermak, Alexander, Ekaterina and Rostislav.

A.A. Baranov ordered the Russian ships to deploy opposite the village. For a whole month, he negotiated with the leaders about the extradition of several prisoners and the renewal of the treaty, but everything was unsuccessful. The Indians moved from their old village to a new settlement at the mouth of the Indian River.

Military operations began. In early October, the Neva brig, commanded by Lisyansky, joined the Baranov flotilla.

After stubborn and prolonged resistance, truce came from the koloshes. After negotiations, the whole tribe left.

On October 8, 1804, the Russian flag was raised over the Indian settlement.

Novoarkhangelsk - the capital of Russian America

Baranov occupied the deserted village and destroyed it. A new fortress was laid here - the future capital of Russian America - Novo-Arkhangelsk. On the shore of the bay, where the old Indian village stood, on a hill, a fortification was built, and then the house of the Ruler, which was called by the Indians - Baranov's Castle.

Only in the autumn of 1805, an agreement was again concluded between Baranov and Scoutlelt. As gifts were presented a bronze double-headed eagle, the Cap of Peace, made by Russians on the model of Tlingit ceremonial hats, and a blue robe with ermines. But for a long time the Russians and Aleuts were afraid to go deep into the impenetrable rain forests of Sitka, this could cost them their lives. From August 1808, Novoarkhangelsk became the main city of the Russian-American Company and the administrative center of Russian possessions in Alaska and remained so until 1867, when Alaska was sold to the USA.

In Novoarkhangelsk there was a wooden fortress, a shipyard, warehouses, barracks, residential buildings. 222 Russians and over 1,000 natives lived here.

The fall of the Russian fort Yakutat

On August 20, 1805, the Eyak warriors of the Tlahaik-Tekuedi (tluhedi) clan, led by Tanukh and Lushvak, and their allies from among the Tlingit of the Kuashkkuan clan burned Yakutat and killed the Russians remaining there. Of the entire population of the Russian colony in Yakutat in 1805, according to official data, 14 Russians “and many more islanders” died, that is, allied Aleuts. The main part of the party, together with Demyanenkov, was sunk in the sea by a storm. About 250 people died then. The fall of Yakutat and the death of Demyanenkov's party became another heavy blow for the Russian colonies. An important economic and strategic base on the coast of America was lost. Thus, the armed actions of the Tlingit and Eyak in 1802-1805. significantly weakened the potential of the RAC. Direct financial damage reached, apparently, no less than half a million rubles. All this stopped the advance of the Russians in a southerly direction along the northwestern coast of America for several years. The Indian threat further fettered the RAC forces in the area of arch. Alexandra did not allow the systematic colonization of Southeast Alaska to begin.

Relapses of confrontation

So, on February 4, 1851, an Indian military detachment from the river. Koyukuk attacked the village of Indians who lived at the Russian loner (factory) Nulato in the Yukon. The loner herself was also attacked. However, the attackers were repulsed with damage. The Russians also had losses: Vasily Deryabin, the head of the trading post, was killed and an employee of the company (Aleut) and an English lieutenant Bernard, who arrived in Nulato from the British military sloop Enterprise to search for the missing members of Franklin's third polar expedition, were mortally wounded. In the same winter, the Tlingit (Sitka Koloshi) staged several quarrels and fights with the Russians in the market and in the forest near Novoarkhangelsk. In response to these provocations, the chief ruler, N. Ya. Rosenberg, announced to the Indians that if the unrest continued, he would order the “Kolosha market” to be closed altogether and interrupt all trade with them. The reaction of the Sitkinites to this ultimatum was unprecedented: on the morning of the next day, they made an attempt to capture Novoarkhangelsk.

We somehow discussed such an interesting question for a long time, about that, and now let's get acquainted with the material, how it all began ...

The development of the lands of Alaska by Russian colonists began at the end of the 18th century. Moving south along the mainland coast of Alaska in search of richer fishing grounds, Russian parties of hunters for sea animals gradually approached the territory inhabited by the Tlingit, one of the most powerful and formidable tribes of the Northwest coast. The Russians called them Koloshi (Kolyuzhs). This name comes from the custom of Tlingit women to insert a wooden plank - kaluga - into the cut on the lower lip, which made the lip stretch and sag. “Angier than the most predatory beasts”, “a murderous and evil people”, “bloodthirsty barbarians” - in such expressions the Russian pioneers spoke about the Tlingits.

And they had their reasons for that.

By the end of the XVIII century. The Tlingit occupied the coast of southeastern Alaska from the Portland Canal in the south to Yakutat Bay in the north, as well as the adjacent islands of the Alexander Archipelago.

The Tlingit country was divided into territorial divisions - kuans (Sitka, Yakutat, Huna, Khutsnuvu, Akoy, Stikine, Chilkat, etc.). In each of them there could be several large winter villages, where representatives of various clans (clans, sibs) lived, belonging to two large phratries of the tribe - Wolf / Eagle and Raven. These clans - Kiksadi, Kagwantan, Deshitan, Tluknahadi, Tekuedi, Nanyaayi, etc. - were often at enmity with each other. It was tribal, clan ties that were the most significant and strong in Tlingit society.

The first clashes between the Russians and the Tlingit date back to 1741, later there were also small skirmishes with the use of weapons.

In 1792, an armed conflict took place on Hinchinbrook Island with an uncertain result: the head of the party of industrialists and the future ruler of Alaska, Alexander Baranov, almost died, the Indians retreated, but the Russians did not dare to gain a foothold on the island and also sailed to Kodiak Island. Tlingit warriors were dressed in wicker wooden kuyaks, elk cloaks and animal-like helmets (apparently made from animal skulls). The Indians were armed mainly with cold and throwing weapons.

If during the attack on the party of A. A. Baranov in 1792 the Tlingits had not yet used firearms, then already in 1794 they had a lot of guns, as well as decent stocks of ammunition and gunpowder.

Treaty of Peace with the Indians of Sitka

Russians in 1795 appear on the island of Sitka, which was owned by the Kiksadi Tlingit clan. Closer contacts began in 1798.

After several minor clashes with small detachments of kiksadi, led by the young military leader Katlean, Alexander Andreevich Baranov concludes an agreement with the leader of the kiksadi tribe, Scoutlelt, to acquire land for the construction of a trading post.

Scoutlelt was baptized and his name became Michael. Baranov was his godfather. Scoutlelt and Baranov agreed to cede part of the land on the coast to the Russians and build a small trading post at the mouth of the Starrigavan River.

The alliance between the Russians and the Kiksadi was beneficial to both sides. The Russians patronized the Indians and helped them protect themselves from other warring tribes.

On July 15, 1799, the Russians began building the fort "St. Michael the Archangel", now this place is called Staraya Sitka.

Meanwhile, the Kiksadi and Deshitan tribes concluded a truce - the enmity between the Indian clans ceased.

The danger to the Kixadi was gone. Too close contact with the Russians is now becoming too burdensome. Both the Kiksadi and the Russians felt this very soon.

Tlingit from other clans who visited Sitka after the cessation of hostilities there, mocked its inhabitants and "boasted of their freedom." The biggest quarrel occurred on Easter, however, thanks to the decisive actions of A.A. Baranov, bloodshed was avoided. However, on April 22, 1800, A.A. Baranov departed for Kodiak, leaving V.G. Medvednikov.

Despite the fact that the Tlingit had rich experience of communicating with Europeans, relations between the Russian settlers and the natives became more and more aggravated, which ultimately led to a protracted bloody war. However, such a result was by no means just an absurd accident or a consequence of the intrigues of insidious foreigners, just as these events were not generated by the only natural bloodthirstiness of the “fierce ears”. The Tlingit Kuans brought other, deeper causes onto the warpath.

Background of the war

Russian and Anglo-American merchants had one goal in the local waters, one main source of profit - furs, sea otters. But the means to achieve this goal were different. The Russians themselves mined precious furs, sending parties of Aleuts after them and founding permanent fortified settlements in the fishing areas. Buying skins from the Indians played a secondary role.

Due to the specifics of their position, British and American (Boston) merchants acted in exactly the opposite way. They periodically came on their ships to the shores of the Tlingit country, conducted an active trade, bought furs and left, leaving the Indians in return for fabrics, weapons, ammunition, and alcohol.

The Russian-American Company could not offer the Tlingit practically any of these goods, which they valued so much. The ban on the sale of firearms among the Russians pushed the Tlingit to even closer ties with the Bostonians. For this trade, the volume of which was constantly growing, the Indians needed more and more furs. However, the Russians with their activities prevented the Tlingit from trading with the Anglo-Saxons.

The active fishing of the sea otter, which was carried out by Russian parties, was the reason for the impoverishment of the natural resources of the region, depriving the Indians of their main commodity in relations with the Anglo-Americans. All this could not but affect the attitude of the Indians towards the Russian colonists. The Anglo-Saxons actively fueled their hostility.

Every year, about fifteen foreign ships took out 10-15 thousand sea otters from the possessions of the RAC, which was equal to four years of Russian fishing. The strengthening of the Russian presence threatened them with deprivation of profits.

Thus, the predatory fishing of the sea animal, which was launched by the Russian-American Company, undermined the basis of the economic well-being of the Tlingit, depriving them of their main commodity in profitable trade with the Anglo-American sea traders, whose inflammatory actions served as a kind of catalyst that hastened the unleashing of the imminent military conflict. The rash and rude actions of Russian industrialists served as an impetus for the unification of the Tlingits in the struggle to expel the RAC from their territories.

In the winter of 1802, a great council of leaders took place in Hutsnuwu-kuan (Father Admiralty), at which a decision was made to start a war against the Russians. The council developed a plan of military action. It was planned with the onset of spring to gather soldiers in Khutsnuva and, after waiting for the fishing party to leave Sitka, attack the fort. The party was to lie in wait in the Dead Strait.

Hostilities began in May 1802 with an attack at the mouth of the Alsek River on the Yakutat fishing party of I.A. Kuskov. The party consisted of 900 native hunters and more than a dozen Russian industrial hunters. The attack of the Indians, after several days of skirmishing, was successfully repulsed. The Tlingit, seeing the complete failure of their warlike plans, went to negotiations and concluded a truce.

The uprising of the Tlingit - the destruction of the Mikhailovsky Fort and the Russian fishing parties

After the fishing party of Ivan Urbanov (about 190 Aleuts) left the Mikhailovsky Fort, 26 Russians, six "Englishmen" (American sailors in the service of the Russians), 20-30 Kodiaks and about 50 women and children remained on Sitka. On June 10, a small artel under the command of Alexei Evglevsky and Alexei Baturin went hunting to the “distant Siuchy stone”. Other inhabitants of the settlement continued to carelessly go about their daily business.

The Indians attacked simultaneously from two sides - from the forest and from the side of the bay, sailing on war canoes. This campaign was led by the military leader of the Kiksadi, the nephew of Scoutlelt, the young leader - Catlian. An armed mob of Tlingit, numbering about 600 people, under the command of the leader of the Sitka Scoutlelt, surrounded the barracks and opened heavy rifle fire at the windows. At the call of Scoutlelt, a huge flotilla of war canoes came out from behind the cape of the bay, on which there were at least 1000 Indian warriors, who immediately joined the Sitkins. Soon the roof of the barracks caught fire. The Russians tried to shoot back, but could not resist the overwhelming superiority of the attackers: the doors of the barracks were knocked out and, despite the direct fire of the cannon that was inside, the Tlingits managed to get inside, kill all the defenders and plunder the furs stored in the barracks

There are various versions of the participation of the Anglo-Saxons in unleashing the war.

In 1802, the East Indian captain Barber landed six sailors on the island of Sitka, allegedly for a mutiny on the ship. They were taken to work in a Russian city.

Having bribed the Indian chiefs with weapons, rum, and knick-knacks during their long winter stay in the Tlingit villages, promising them gifts if they drove the Russians from their island, and threatening not to sell guns and whiskey, Barber played on the ambitions of the young military leader Catlean. The gates of the fort were opened from the inside by American sailors. So, naturally, without warning or explanation, the Indians attacked the fortress. All defenders, including women and children, were killed.

According to another version, the real instigator of the Indians should be considered not the Englishman Barber, but the American Cunningham. He, unlike Barber and the sailors, ended up on Sitka clearly not by chance. There is a version that he was initiated into the plans of the Tlingit, or even participated directly in their development.

The fact that foreigners will be declared responsible for the Sitka disaster was predetermined from the very beginning. But the reasons for the fact that the Englishman Barber was then recognized as the main culprit lie probably in the uncertainty in which Russian foreign policy was in those years.

The fortress was completely destroyed, and the entire population was exterminated. Nothing is being built there yet. The losses for Russian America were significant, for two years Baranov was gathering strength in order to return to Sitka.

The news of the destruction of the fortress was brought to Baranov by the English captain Barber. At Kodiak Island, he put out 20 guns from the side of his ship, the Unicorn. But, afraid to get involved with Baranov, he went to the Sandwich Islands - to trade with the Hawaiians the good looted in Sitka.

A day later, the Indians almost completely destroyed the small party of Vasily Kochesov, who was returning to the fortress from the sea lions.

The Tlingit had a special hatred for Vasily Kochesov, the famous hunter, known among the Indians and Russians as an unsurpassed marksman. The Tlingit called him Gidak, which probably comes from the Tlingit name of the Aleuts, whose blood flowed in Kochesov's veins - giyak-kwaan (the hunter's mother was from the Fox Range Islands). Having finally got the hated archer into their hands, the Indians tried to make his death, like the death of his comrade, as painful as possible. According to K.T. Khlebnikov, “the barbarians, not suddenly, but temporarily, cut off their nose, ears and other members of their body, stuffed their mouths with them, and viciously mocked the torment of the sufferers. Kochesov ... could not endure pain for a long time and was happy at the end of his life, but the unfortunate Eglevsky languished in terrible torment for more than a day.

In the same year, 1802: Ivan Urbanov's Fishing Sitka party (90 kayaks) was tracked down by the Indians in the Frederick Strait and attacked on the night of June 19-20. Lurking in ambushes, the warriors of Kuan Keik-Kuyu did not betray their presence in any way and, as K.T. Khlebnikov wrote, “the leaders of the party did not notice any troubles or reasons for displeasure ... But this silence and silence were the harbingers of a cruel thunderstorm.” The Indians attacked the party members at the lodging for the night and "almost killed them with bullets and daggers." 165 Kodiaks were killed in the massacre, and this was no less a heavy blow to the Russian colonization than the destruction of the Mikhailovskaya fortress.

Russian return to Sitka

Then came 1804, the year the Russians returned to Sitka. Baranov learned that the first Russian round-the-world expedition had set out to sea from Kronstadt, and he was looking forward to the arrival of the Neva in Russian America, while at the same time building a whole fleet of ships.

In the summer of 1804, the ruler of the Russian possessions in America, A.A. Baranov went to the island with 150 industrialists and 500 Aleuts in his kayaks and with the ships Ermak, Alexander, Ekaterina and Rostislav.

A.A. Baranov ordered the Russian ships to deploy opposite the village. For a whole month, he negotiated with the leaders about the extradition of several prisoners and the renewal of the treaty, but everything was unsuccessful. The Indians moved from their old village to a new settlement at the mouth of the Indian River.

Military operations began. In early October, the Neva brig, commanded by Lisyansky, joined the Baranov flotilla.

After stubborn and prolonged resistance, truce came from the koloshes. After negotiations, the whole tribe left.

On October 8, 1804, the Russian flag was raised over the Indian settlement.

Novoarkhangelsk - the capital of Russian America

Baranov occupied the deserted village and destroyed it. A new fortress was laid here - the future capital of Russian America - Novo-Arkhangelsk. On the shore of the bay, where the old Indian village stood, on a hill, a fortification was built, and then the house of the Ruler, which was called by the Indians - Baranov's Castle.

Only in the autumn of 1805, an agreement was again concluded between Baranov and Scoutlelt. As gifts were presented a bronze double-headed eagle, the Cap of Peace, made by Russians on the model of Tlingit ceremonial hats, and a blue robe with ermines. But for a long time the Russians and Aleuts were afraid to go deep into the impenetrable rainforests of Sitka, this could cost them their lives.

Novoarkhangelsk (most likely the beginning of the 1830s)

From August 1808, Novoarkhangelsk became the main city of the Russian-American Company and the administrative center of Russian possessions in Alaska, and remained so until 1867, when Alaska was sold to the United States.

In Novoarkhangelsk there was a wooden fortress, a shipyard, warehouses, barracks, residential buildings. 222 Russians and over 1,000 natives lived here.

The fall of the Russian fort Yakutat

On August 20, 1805, the Eyak warriors of the Tlahaik-Tekuedi (tluhedi) clan, led by Tanukh and Lushvak, and their allies from among the Tlingit of the Kuashkkuan clan burned Yakutat and killed the Russians remaining there. Of the entire population of the Russian colony in Yakutat in 1805, according to official data, 14 Russians “and many more islanders” died, that is, allied Aleuts. The main part of the party, together with Demyanenkov, was sunk in the sea by a storm. About 250 people died then. The fall of Yakutat and the death of Demyanenkov's party became another heavy blow for the Russian colonies. An important economic and strategic base on the coast of America was lost.

Thus, the armed actions of the Tlingit and Eyak in 1802-1805. significantly weakened the potential of the RAC. Direct financial damage reached, apparently, no less than half a million rubles. All this stopped the advance of the Russians in a southerly direction along the northwestern coast of America for several years. The Indian threat further fettered the RAC forces in the area of arch. Alexandra did not allow the systematic colonization of Southeast Alaska to begin.

Relapses of confrontation

So, on February 4, 1851, an Indian military detachment from the river. Koyukuk attacked the village of Indians who lived at the Russian loner (factory) Nulato in the Yukon. The loner herself was also attacked. However, the attackers were repulsed with damage. The Russians also had losses: Vasily Deryabin, the head of the trading post, was killed and an employee of the company (Aleut) and an English lieutenant Bernard, who arrived in Nulato from the British military sloop Enterprise to search for the missing members of Franklin's third polar expedition, were mortally wounded. In the same winter, the Tlingit (Sitka Koloshi) staged several quarrels and fights with the Russians in the market and in the forest near Novoarkhangelsk. In response to these provocations, the chief ruler, N. Ya. Rosenberg, announced to the Indians that if the unrest continued, he would order the “Kolosha market” to be closed altogether and interrupt all trade with them. The reaction of the Sitkinites to this ultimatum was unprecedented: on the morning of the next day, they made an attempt to capture Novoarkhangelsk. Some of them, armed with guns, sat down in the bushes near the fortress wall; the other, having placed prefabricated ladders to a wooden tower with cannons, the so-called "Koloshenskaya battery", almost took possession of it. Fortunately for the Russians, the sentries were on the alert and sounded the alarm just in time. An armed detachment that came to the rescue threw down three Indians who had already climbed onto the battery, and stopped the rest.

In November 1855, another incident occurred when several natives captured Andreevskaya alone in the lower Yukon. At that time, its manager, the Kharkov tradesman Alexander Shcherbakov, and two Finnish workers who served in the RAC were here. As a result of a sudden attack, the kayaker Shcherbakov and one worker were killed, and the loner was looted. The surviving RAC officer Lavrenty Keryanin managed to escape and safely reach the Mikhailovsky redoubt. A punitive expedition was immediately dispatched to find the natives hiding in the tundra who had ravaged the Andreevskaya loneliness. They sat down in a barabora (Eskimo half-dugout) and refused to give up. The Russians were forced to open fire. As a result of the skirmish, five natives were killed, and one managed to escape.

Let's remember just such a story as they tried and more. Here is another story, and just recently there was such news on the Internet that The original article is on the website InfoGlaz.rf Link to the article from which this copy is made -

Russo-Indian War in Alaska

On September 16, 1821, the Russian Empire officially confirmed its exclusive rights to Alaska. It is believed that the Russian settlers were not too zealous in the development of Alaska, however, there are many interesting facts that indicate the opposite.

.jpg)

1. From Ivan the Terrible to Alaska

It is believed that Russian people first appeared in Alaska in the 18th century, and they were members of the expedition of Pavlutsky and Shestakov from the ship St. Gabriel. I was looking for the North American coast and Vitus Bering. But the Russian traveler Jakob Lindenau, who explored Siberia, wrote back in 1742 that the Chukchi “go to Alaska by boats” and “from that land they bring wooden dishes similar to Russian ones.”

In 1937, scientists found an ancient settlement in Cook Inlet off the southern coast of Alaska. The researchers found that Russians lived in the huts, moreover, it was more than three centuries ago. It turns out that our ancestors arrived in America under Ivan the Terrible.

But the Americans themselves go even further. In the history of the state of Alaska, it is reported that the first people came here from Siberia about twenty thousand years ago. They came because at that time there was an isthmus between North America and Eastern Eurasia, located where the Bering Strait is today. By the appearance of the first Europeans, indigenous peoples formed from the settlers - the Eskimos, Aleuts, Athabaskans, Haida, Tlingit, etc.

2. "Pizarro Russian"

.png)

Merchant became the first ruler of Russian lands in America Alexander Andreevich Baranov.

There would be no happiness, but misfortune helped. His ship crashed off the coast of Alaska. Baranov himself, along with the surviving members of the team, rowed on the wreckage for a long time and eventually sailed to Kodiak Island.

Baranov began the development of Alaska and ruled here for 28 years. With his direct participation, such Russian settlements as Fort Ross and Novoarkhangelsk were erected, where Alexander Andreevich subsequently transferred the capital of Russian America from Irkutsk. Baranov's energy was truly inexhaustible. Thanks to him, Alaska began to trade with the Hawaiian Islands and even China! He founded a shipyard, began to mine coal, built a copper smelter.

Baranov himself proudly called himself "Russian Pizarro". However, the unspoken title "Father of Alaska" suited him better. Paul I himself awarded Alexander Andreevich with a nominal medal for hard work and services to the fatherland.

3. Russian-Indian war

Even earlier than Baranov, Russian researcher Grigory Ivanovich Shelikhov was engaged in the development of navigation between the Kuril and Aleutian ridges.

When he set out to establish a village on the same island of Kodiak, they began to dissuade him, since the locals had killed several dozen Russian hunters not long before. The Eskimos also offered resistance to Shelikhov himself. But he did not listen to anyone, he founded the village, after which he made a real massacre. According to various sources, from 500 to 2500 Eskimos were killed during clashes with the natives. More than a thousand people Shelikhov took prisoner.

Baranov faced similar problems. Once the Tlingit Indians, who were famous for their militancy and terrified other tribes, cut out a Russian settlement. Of the eighty people, only one survived. The Russian Pissarro responded two years later, waiting for reinforcements from the Krusenstern expedition. The clashes took place within the framework of the Russian-Indian War (it turns out that there was one), which lasted from 1802 to 1805. In battle, the Tlingit looked creepy. They wore elk cloaks and beast-like helmets. But how could this scare a Russian peasant who went to bear!

Actually, on the site of one of the destroyed Tlingit settlements, Alexander Andreevich founded Novoarkhangelsk (later Sitka). The conquered Indians presented Baranov with a golden helmet as a sign of peace.

4. "The Apostle of Alaska"

Despite the truce, tensions between the Russian settlers and the Indians remained. Missionaries from the Russian church helped smooth it out. The most famous of them is Father Innokenty Veniaminov, who was nicknamed the "Apostle of Alaska."

Father Innokenty became famous for the fact that he read sermons not only in Russian, but also in Tlingit. "The Apostle of Alaska" studied and compiled the alphabet of the Aleuts, opened a school for children.

The Indians were quite willing to accept Christianity. Moreover, this made them equal to the Russian settlers, and the same Aleuts could no longer be used as cheap labor. Officially, serfdom did not exist in Alaska, but the Russians treated the Indians as if they were forced servitude. Therefore, the same Baranov at first opposed the too rapid churching of the natives.

From the Aleutian Islands, Father Innokenty moved to Alaska, where he began the Christianization of the Indians from the Koloshi tribe. Veniaminov translated the Gospel of Matthew into the languages of the locals, including the Kodiaks.

5. No beavers, no whales

As you know, in 1867 Alaska was sold to the United States of North America for $7.2 million. Is it big money? It turns out that for the Russian Empire it was mere pennies. Alaska was sold for about 11 million rubles, while Russia's GDP was 400 million rubles a year.

You are even more surprised by the deal when you find out that, according to the same Baranov, only beavers in the first decade of the 19th century in Alaska were mined for 4.5 million rubles. And the annual whaling off the coast of Alaska, according to Russian researcher Novikov, brought 8 million dollars.

Nevertheless, the Russian press of the time called the deal very smart. Although even its supporters grumbled that the importance of the treaty "will not be understood immediately." It seems that they still do not understand.

The development of the lands of Alaska by Russian colonists began at the end of the 18th century. Moving south along the mainland coast of Alaska in search of richer fishing grounds, Russian parties of hunters for sea animals gradually approached the territory inhabited by the Tlingit, one of the most powerful and formidable tribes of the Northwest coast.

The Russians called them Koloshi (Kolyuzhs). This name comes from the custom of Tlingit women to insert a wooden plank - kaluga - into the cut on the lower lip, which made the lip stretch and sag.

“More evil than the most predatory animals”, “a murderous and evil people”, “bloodthirsty barbarians” - in such expressions the Russian pioneers spoke about the Tlingits. And they had their reasons for that.

By the end of the XVIII century. The Tlingit occupied the coast of southeastern Alaska from the Portland Canal in the south to Yakutat Bay in the north, as well as the adjacent islands of the Alexander Archipelago.

The Tlingit country was divided into territorial divisions - kuans (Sitka, Yakutat, Huna, Khutsnuvu, Akoy, Stikine, Chilkat, etc.). Each of them could have several large winter villages, where representatives of various clans (clans, sibs) lived, belonging to two large phratries of the tribe - the Wolf / Eagle and the Raven. These clans - Kiksadi, Kagwantan, Deshitan, Tluknahadi, Tekuedi, Nanyaayi, etc. - were often at enmity with each other.

It was tribal, clan ties that were the most significant and strong in Tlingit society.

.png)

The first clashes between the Russians and the Tlingit date back to 1741, later there were also small skirmishes with the use of weapons.

In 1792, an armed conflict took place on Hinchinbrook Island with an uncertain result: the head of the party of industrialists and the future ruler of Alaska, Alexander Baranov, almost died, the Indians retreated, but the Russians did not dare to gain a foothold on the island and also sailed to Kodiak Island. Tlingit warriors were dressed in wicker wooden kuyaks, elk cloaks and animal-like helmets (apparently made from animal skulls). The Indians were armed mainly with cold and throwing weapons.

If during the attack on the party of A. A. Baranov in 1792 the Tlingits had not yet used firearms, then already in 1794 they had a lot of guns, as well as decent stocks of ammunition and gunpowder.

Treaty of Peace with the Indians of Sitka

Russians in 1795 appear on the island of Sitka, which was owned by the Kiksadi Tlingit clan. Closer contacts began in 1798.

After several small skirmishes with small detachments of kiksadi, led by a young war leader Kotlean, Alexander Andreevich Baranov concludes an agreement with the leader of the Kiksadi tribe, Scoutlelt, on the acquisition of land for the construction of a trading post.

Scoutlelt was baptized and his name became Michael. Baranov was his godfather. Scoutlelt and Baranov agreed to cede part of the land on the coast to the Russians and build a small trading post at the mouth of the Starrigavan River.

The alliance between the Russians and the Kiksadi was beneficial to both sides. The Russians patronized the Indians and helped them protect themselves from other warring tribes.

On July 15, 1799, the Russians began building the fort "St. Michael the Archangel", now this place is called Staraya Sitka.

_by_Postels.jpg)

Meanwhile, the Kiksadi and Deshitan tribes concluded a truce - the hostility between the Indian clans ceased.

The danger to the Kixadi was gone. Too close contact with the Russians is now becoming too burdensome. Both the Kiksadi and the Russians felt this very soon.

Tlingit from other clans who visited Sitka after the cessation of hostilities there, mocked its inhabitants and "boasted of their freedom." The biggest quarrel occurred on Easter, however, thanks to the decisive actions of A.A. Baranov, bloodshed was avoided. However, on April 22, 1800, A.A. Baranov departed for Kodiak, leaving V.G. Medvednikov.

Despite the fact that the Tlingit had rich experience of communicating with Europeans, relations between the Russian settlers and the natives became more and more aggravated, which ultimately led to a protracted bloody war. However, such a result was by no means just an absurd accident or a consequence of the intrigues of insidious foreigners, just as these events were not generated by the only natural bloodthirstiness of the “fierce ears”. The Tlingit Kuans brought other, deeper causes onto the warpath.

Background of the war

Russian and Anglo-American merchants had one goal in the local waters, one main source of profit - furs, sea otters.

But the means to achieve this goal were different. The Russians themselves mined precious furs, sending parties of Aleuts after them and founding permanent fortified settlements in the fishing areas. Buying skins from the Indians played a secondary role.

Due to the specifics of their position, British and American (Boston) merchants acted in exactly the opposite way. They periodically came on their ships to the shores of the Tlingit country, conducted an active trade, bought furs and left, leaving the Indians in return for fabrics, weapons, ammunition, and alcohol.

The Russian-American Company could not offer the Tlingit practically any of these goods, which they valued so much. The ban on the sale of firearms among the Russians pushed the Tlingit to even closer ties with the Bostonians. For this trade, the volume of which was constantly growing, the Indians needed more and more furs. However, the Russians with their activities prevented the Tlingit from trading with the Anglo-Saxons.

The active fishing of the sea otter, which was carried out by Russian parties, was the reason for the impoverishment of the natural resources of the region, depriving the Indians of their main commodity in relations with the Anglo-Americans. All this could not but affect the attitude of the Indians towards the Russian colonists. The Anglo-Saxons actively fueled their hostility.

Every year, about fifteen foreign ships took out 10-15 thousand sea otters from the possessions of the RAC, which was equal to four years of Russian fishing. The strengthening of the Russian presence threatened them with deprivation of profits.

Thus, the predatory fishing of the sea animal, which was launched by the Russian-American Company, undermined the basis of the economic well-being of the Tlingit, depriving them of their main commodity in profitable trade with the Anglo-American sea traders, whose inflammatory actions served as a kind of catalyst that hastened the unleashing of the imminent military conflict. The rash and rude actions of Russian industrialists served as an impetus for the unification of the Tlingits in the struggle to expel the RAC from their territories.

In the winter of 1802, a great council of leaders took place in Hutsnuwu-kuan (Father Admiralty), at which a decision was made to start a war against the Russians. The council developed a plan of military action.

.jpg)

It was planned with the onset of spring to gather soldiers in Khutsnuva and, after waiting for the fishing party to leave Sitka, attack the fort. The party was to lie in wait in the Dead Strait.

Hostilities began in May 1802 with an attack at the mouth of the Alsek River on the Yakutat fishing party of I.A. Kuskov. The party consisted of 900 native hunters and more than a dozen Russian industrial hunters.

The attack of the Indians, after several days of skirmishing, was successfully repulsed. The Tlingit, seeing the complete failure of their warlike plans, went to negotiations and concluded a truce.

See the continuation on the website: For Advanced - Battles - Russian-Indian War 1802-1805 Part II

We still remember and mourn the sale of Alaska to the Americans. But few people know that one of the reasons for the loss of Russian America was the bloody and bitter war between the Russian colonists and the desperate Indians of the Tlingit tribe. What role did Russia's trade with China play in this confrontation? Who stood behind the backs of the Indians fighting the Russians? What does the Soviet rock opera "Juno and Avos" have to do with those events? Why did the conflict between Russia and the Tlingit formally end only under Putin? recalls the little-known pages of the development and loss of Russian Alaska.

Russia all the way to Vancouver

The Russian colonization of North America in the 18th-19th centuries was very different from the conquest of other territories of the empire. If, for example, in Siberia, voivodes and archers always followed the Cossacks and merchants, then in 1799 the government handed over Alaska to the private-state monopoly - the Russian-American Company (RAC). This decision largely determined not only the features of the Russian development of this vast territory, but also its final result - the forced sale of Alaska to the United States of America in 1867.

One of the main obstacles to the active colonization of Alaska was the bloody and bitter conflict between Russian settlers and the warlike Indian tribe of the Tlingit at the beginning of the 19th century. This confrontation later had serious consequences: because of it, the penetration of Russians deep into the American mainland stopped for many years. In addition, after that, Russia was forced to abandon its ambitious plans to seize the Pacific coast southeast of Alaska up to Vancouver Island (now the territory of the Canadian province of British Columbia).

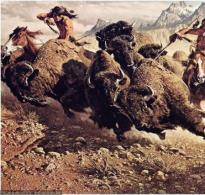

Skirmishes between Russians and Tlingits (our colonists called them kolosh or kolyuzh) regularly took place at the end of the 18th century, but a full-scale war broke out in 1802 with a sudden attack by Indians on a fortress on Sitka Island (now Baranova Island). Modern researchers name several reasons for it. Firstly, as part of the fishing parties, the Russians brought to the land of the Tlingits their long-time worst enemies - the Eskimos-Chugachs. Secondly, the attitude of newcomers to the natives was not always, to put it mildly, respectful. According to Lieutenant of the Russian Navy Gavriil Davydov, “the treatment of the Russians in Sitka could not give the kolyuzhs a good opinion of them, because the industrial ones began to take away their girls and do them other insults.” The Tlingit were also dissatisfied with the fact that the Russians, while fishing in the straits of the archipelago, often appropriated Indian food supplies.

But the main reason for the hostility of the Tlingit to Russian industrialists was different. Initially, our "conquistadors" came to the coast of Alaska to harvest sea otters (sea beavers) and sell their fur to China. As the modern Russian historian Alexander Zorin writes, “The predatory sea animal hunt that the Russian-American Company launched undermined the basis of the economic well-being of the Tlingit, depriving them of their main commodity in profitable trade with Anglo-American sea traders, whose inflammatory actions served as a kind of catalyst that accelerated the unleashing of imminent military conflict. The rash and rude actions of the Russians served as an impetus for the unification of the Tlingits in the struggle to expel the RAC from their territories. This struggle resulted in an open war against Russian settlements and fishing parties, which the Tlingit waged both as part of extensive alliances and by the forces of individual clans.

American intrigues

And indeed, in the unfolding fierce competition for sea fishing off the northwestern coast of North America, the local Indians saw the Russians as their main enemies, who came here seriously and for a long time. The British and Americans only occasionally visited here on ships, so they posed a much smaller threat to the natives. In addition, they exchanged valuable fur with the Indians for European goods, including firearms. And the Russians in Alaska themselves mined fur and had little to offer the Tlingits in return. In addition, they themselves were desperate for European goods.

Historians still argue about the role of the Americans (in Russia they were then called Bostonians) in provoking the Indian uprising against Russia in 1802. Academician Nikolai Bolkhovitinov does not deny the role of this factor, but believes that the "intrigues of the Bostonians" were deliberately exaggerated by the leadership of the Russian-American Company, but in fact "most of the British and American captains took a neutral position or treated the Russians favorably." Nevertheless, one of the immediate reasons for the action of the Tlingit was the actions of the captain of the American ship "Globe" William Cunningham. He threatened the Indians with a complete cessation of all trade with them if they did not get rid of the Russian presence on their land.

As a result, in June 1802, the Tlingits, in the amount of one and a half thousand, unexpectedly attacked and burned the fortress of Michael the Archangel on the island of Sitka, destroying its small garrison. It is curious that several American sailors participated in both the defense of the Russian settlement and the attack on it, and some of them deserted from the American ship Jenny, commanded by Captain John Crocker. The next day, also taking advantage of the surprise factor, the Indians killed the fishing party returning to the fortress, and the captured half-breed Creoles Vasily Kochesov and Alexei Evglevsky were tortured to death by torture. A few days later, the Tlingits killed 168 people from the Sitka party of Ivan Urbanov. The surviving Russians, Kodiaks and Aleuts, including women and children rescued from captivity, were taken on board by the nearby British brig Unicorn and two American ships - the Alert and the notorious Globe. As Bolkhovitinov bitterly notes, his captain, William Cunningham, wanted "apparently to admire the results of his anti-Russian agitation."

The loss of Sitka was a heavy blow to the chief ruler of the Russian colonies in North America. He hardly resisted immediate revenge and decided to accumulate forces for a retaliatory strike against the Tlingit. Having collected an impressive flotilla of three ships and 400 native kayaks, in April 1804 Baranov set off on a punitive expedition against the Tlingit. He deliberately built his route not along the shortest path, but along a huge arc, in order to visually convince the local Indians of Russian power and the inevitability of punishment for the ruin of Sitka. He succeeded - when the Russian squadron approached, the Tlingits left their villages in a panic and hid in the forests. Soon the sloop-of-war "Neva" joined Baranov, who under the command of the famous captain Yuri Lisyansky made a round-the-world trip. The outcome of the battle was predetermined - the Tlingits were defeated, and instead of the fortress of Michael the Archangel destroyed by them, Baranov founded the settlement of Novo-Arkhangelsk, which became the capital of Russian America (now it is the city of Sitka).

However, the confrontation between the Russian-American Company and the Indians did not end there - in August 1805, the Tlingits destroyed the Russian fortress of Yakutat. The news of this caused ferment among the native inhabitants of Alaska. The prestige of Russia, so hard restored among them, was again under threat. According to Bolkhovitinov, during the war of 1802-1805, about fifty Russians and “and with them many more islanders,” that is, natives allied to them, died. How many people the Tlingits lost, of course, no one counted.

New owners

Here it is necessary to answer a logical question - why did the possessions of the huge and powerful Russian Empire turn out to be so vulnerable to the attacks of a relatively small tribe of wild Indians? There were two reasons for this, closely related. Firstly, the actual Russian population of Alaska then amounted to several hundred people. Neither the government nor the Russian-American Company bothered to settle and develop this vast territory economically. For comparison: a quarter of a century before, over 50 thousand loyalists moved from the south to Canada alone - British colonists who remained loyal to the English king and did not recognize the independence of the United States. Secondly, the Russian settlers were sorely lacking equipment and modern weapons, while the British and Americans regularly supplied the Tlingit opposing them with guns and even cannons. A Russian diplomat who visited Alaska on an inspection trip in 1805 noted that the Indians "have English guns, while we have Okhotsk guns, which are never used anywhere because they are worthless."

While in Alaska, in September 1805, Rezanov bought the three-masted brigantine "Juno" from the American captain John D "Wolfe, who came to Novo-Arkhangelsk, and in the spring of the following year, the eight-gun tender "Avos" was solemnly launched from the stocks of the local shipyard. On these ships in In 1806, Rezanov set off from Novo-Arkhangelsk to the Spanish fort of San Francisco.He hoped to negotiate with the Spaniards, who then owned California, on trade food supplies for Russian America.We know this whole story from the popular rock opera Juno and Avos, a romantic the plot of which is based on real events.

The 1805 truce between Baranov and the supreme leader of the Tlingit clan, the Kiksadi, Katlian, fixed the fragile status quo in the region. The Indians failed to expel the Russians from their territory, but they managed to defend their freedom. In turn, the Russian-American Company, although it was forced to reckon with the Tlingit, was able to maintain its marine fishery on their lands. Armed skirmishes between Indians and Russian industrialists repeatedly occurred throughout the subsequent history of Russian America, but each time the RAC administration managed to localize them, without bringing the situation to a large-scale war, as in 1802-1805.

The transition of Alaska to the jurisdiction of the United States was met with indignation by the Tlingit. They believed that the Russians had no right to sell their lands. When the Americans later entered into conflicts with the Indians, they always acted in their own manner: they immediately responded to any attempts at resistance with punitive raids. The Tlingit were very happy when, in 1877, the United States temporarily withdrew its military contingent from Alaska to fight the Nez Perce Indians in Idaho. They innocently decided that the Americans left their lands forever. Left without armed protection, the American administration of Sitka (as Novo-Arkhangelsk was now called) hastily gathered a militia from local residents, mainly of Russian origin. Only thanks to this, a repetition of the massacre of 75 years ago was avoided.

Photo: Luc Novovitch / Globallookpress.com

It is curious that the history of the Russian-Tlingit confrontation did not end with the sale of Alaska to the Americans. The natives did not recognize the formal truce of 1805 between Baranov and Katlian, since it was concluded without observing the relevant Indian rites. And only in October 2004, at the initiative of the elders of the Kiksadi clan and the American authorities, a symbolic ceremony of reconciliation between Russia and the Indians took place in the sacred Tlingit clearing. Russia was represented by Irina Afrosina, the great-great-great granddaughter of Alexander Baranov, the first chief ruler of the Russian colonies in North America.

For a thousand-year history, the Russian army fought with many people. But perhaps the most exotic were the wars with the American Indians.

Proud Tlingit

Having barely mastered the Amur region and the shores of Chukotka with Kamchatka, Russian merchants and hunters moved beyond the Bering Strait. In 1732, they discovered Alaska, and now their path lay further south, along the western coast of North America.

The Russians already had considerable experience of contacts with the northern peoples. The Eskimos, for example, got along well. At first they quarreled with the Aleuts, but then they lived peacefully. And military operations against the Chukchi for the Russians ended twice in complete defeat.

The coast of southeastern Alaska was occupied by the Indian people - the Tlingit. They were divided into phratries, phratries into clans, and clans into kuans (groups of related families). Each village had its own leader, its own shaman, free people and slaves.

The Tlingits were engaged in hunting and fishing, but they knew the beginnings of the craft. With neighbors they could both trade and fight. Moreover, the Tlingits used human sacrifices, for which slaves were always required.

Every man among the Tlingit was considered a warrior, for which he was trained from the age of three. They were forced to swim in icy water, sleep in the snow or in the branches of trees, not eat for weeks, endure pain. And, of course, own a weapon.

In war, the Tlingit used bows and arrows with iron tips, copper and iron daggers, clubs with a stone striker, helmets with a visor and wooden protective shells. Favorite methods in battle were a surprise attack at dawn and hand-to-hand combat. Sometimes they assembled fleets of up to a hundred canoes. The neighbors feared and respected the Tlingit.

When they first encountered the Russians, there were about 15,000 of them. The third is warriors. That's just the war has never been considered a common cause for all. In rare cases, the phratry united. More often each kuan stood for himself.

First battles

The first meeting took place in the summer of 1741 on Jacobi Island. 15 sailors from the St. Paul packet boat landed on the shore, seeing the smoke of a fire. Nobody came back. It is believed that the sailors were killed or captured by the Indians.

The second time everything went pretty peacefully. Grigory Shelikhov's detachment explored Yakutat Bay and established relations with the Tlingit.

But the farther south the alien hunters climbed, the less friendly they were met. The Tlingit did not like Russian attempts to establish permanent trading posts. The Indians, accustomed to living in harmony with nature, were also outraged by the barbaric methods of catching a sea animal.

But most of all, the Tlingits were worried that the Eskimos-Chugachs and Aleuts, their sworn enemies, came to their lands with the Russians.

In the summer of 1792, the Tlingits from the Yakutat-Kuan went on a raid against the Chugachs. On the way, they stumbled upon the camp of the chief ruler of Russian America, Alexander Baranov, on Nuchek Island. At night, they imperceptibly crept close to the guards and rushed to the attack - hand-to-hand combat began. The weapons of the Chugach did not take Tlingit armor, and they fled in horror.

The Russians also did not immediately figure out where to aim their guns. The bullets did not really penetrate either body armor or wooden helmets. The battle dragged on for two hours, the Tlingits did not flinch even under the fire of a single Russian cannon. As a result, the Indians nevertheless retreated, carrying away the bodies of 12 dead and wounded. 15 Chugachs died, two Russians.

Baranov asked the authorities "as much cuirass armor and guns as possible, and especially guns and gunpowder." But the Tlingit turned out to be no more stupid than Baranov. They also began to buy guns and gunpowder - from the British and Spaniards, who increasingly appeared in their area.

The Russians had a severe ban on the sale of firearms to the natives. They did not even give it to their henchmen - the Chugachs. In addition, almost all the weapons sent from Russia were unusable. On the other hand, American and British merchants were happy to sell everything that could interest them to the Tlingits.

The death of Novoarkhangelsk

The Russians tried to improve relations with the Indians, tried to join their way of life and even moderated the ardor of their priests, who wanted to immediately baptize everyone and everything.

In 1799, the Russian-American Company was formed. All power over the American possessions of Russia passed to her.

It was headed by Baranov, who was already opposed to the Tlingit. He considered it the most important task to establish a powerful stronghold in the new territories - a real city with a permanent population. The choice fell on the island of Sitka, where the Novoarkhangelsk fort was laid.

Sitka was the "ancestral domain" of the two strongest Tlingit kuans. In the winter of 1802, at their request, a council of all Indian chiefs was held. We decided to start a war with the Russians.

Interestingly, the council was attended by the captains of two American schooners. They gave the Indians a huge shipment of guns and ammunition, as well as two or three cannons. But, most importantly, the Americans directly incited the Tlingit to attack the Russians, saying that they would not bring more of their ships for trade if Novoarkhangelsk was not exterminated.

With the help of foreigners, the Indians drew up a plan for the campaign. They wanted to wait until large fishing parties went to sea, and then attack Yakutat and Novoarkhangelsk. Special "flying flotillas" were allocated to intercept fishermen at sea.

On May 23, the Tlingit began to act. They fulfilled almost everything planned: they took and burned Novoarkhangelsk and its citadel, killed several fishing parties.

The loss of Sitka was a real blow to the ambitious Baranov. He gathered all available forces in Yakutat and decided to counterattack. But other industrialists dissuaded him.

Alcohol is the head of everything

26 Russians and 300 Aleuts were killed in the battles. Ammunition and weapons turned out to be unusable - bullets did not even pierce wooden armor. There are few guns left, and even less gunpowder for them. The Aleut allies were afraid of the Tlingit to death, and especially their leaders Tanukh and Katliuan, whose squads did not know defeat.

It seemed that the Russians in America could not resist. Moreover, entire fleets of the British and Americans were already looming around Sitka and other islands. And then Baranov did not give a damn about all the principles that guided the Russians before.

The Aleuts were given firearms. They stopped waiting for the Indians to attack, they began to attack themselves. At the same time, Baranov ordered the use of naval artillery without restrictions: on single canoes, on armed Tlingits, on coastal villages.

Already in August 1804, the Russians recaptured Sitka. The Indians built a wooden fortress there, but two hours of bombardment rendered its defense useless. The Union of Kuans began to quickly fall apart - Catliuan entered into an alliance with the Russians.

Only Tanukh continued the struggle. In August 1805, he was able to capture Yakutat by cunning and kill a large Russian garrison, but this was already a swan song. Several warships arrived in Alaska. The number of armed Russians grew and amounted to about 1,500 people. The Tlingit turned to guerrilla warfare, which gradually subsided. Peace was soon made with most of the Kuans.

Baranov, on the other hand, decided to do what the British did with the Indians, but the Russians had never done before. The Tlingit began to be introduced to alcohol. So after 25 years, only a pale shadow remained from the warlike tribe. For example, in 1851, the Tlingit decided to raise an uprising on Sitka and even laid siege to the citadel. But as soon as the head of the store, Nikolai Rosenberg, threatened that he would forbid selling alcohol to the Indians, the formidable warriors went home.